My previous post discussed what ports are, where they can be found on FreeBSD and what the files of which a port is composed of look like. This post will now detail how to use ports to build software on FreeBSD (the other BSDs have ports trees that work somewhat similar but are not identical. There are important differences!).

Packages and ports: A word of warning

The ports system works hand in hand with FreeBSD’s package manager Pkg. It makes little difference if some software on your machine was installed via a package or directly from ports – packages are in fact actually built from ports! Still it is not really recommended to mix packages and ports. In past times it was strongly discouraged. Things have changed since then. I’ve done it a lot – and mostly got away with it. Don’t rely on it, though, especially if you’re new to the whole topic. Feel free to do it on a test system and be completely happy – or face subtle and annoying breakage. You cannot know up front.

What’s the deal here? Modern software is a complex thing. Most programs rely on other programs or external libraries. A lot of programs can be configured at run time in certain ways. There are however decisions about program functionality that have to be made at compile time. The ports system allows you to build software with compile-time options other than the default. Pre-compiled packages have no chance to know that you choose to deactivate an option when you built a library yourself that they make use of. They assume that this feature is present (it was available on the system the package was built on after all!). And what can one poor program do in that case? Crash, explode, malfunction… A lot of things.

And then there’s the problem of mixing versions which can lead to all kinds of fun. If you stick with either ports or packages, you always have a consistent system with versions that are known to play together well (as long as the maintainers do their job well – we’re all humans and errors do occur).

Just keep that in mind when thinking about mixing programs installed from packages and ports on one system. You can do that. But it doesn’t mean you should. Enabling more options is generally safer than removing ones set by default. It can still have consequences. This is Unix though. Do whatever you see fit – and claim the responsibility. Your choice.

Most basic ports building

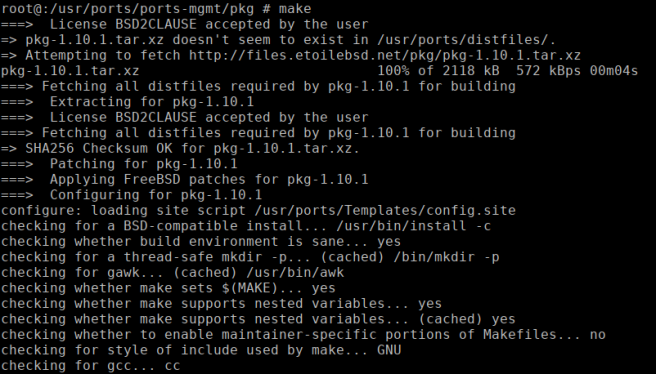

Building a software from ports is extremely easy. Go to the directory of a port and type make. Yes, that’s all! Let’s assume the port has no unsatisfied dependencies. The ports system will then check to see if the source code tarball is present in /usr/ports/distfiles. If it isn’t, it will automatically download it. Then it extracts the source code, prepares everything for the compilation and compiles it.

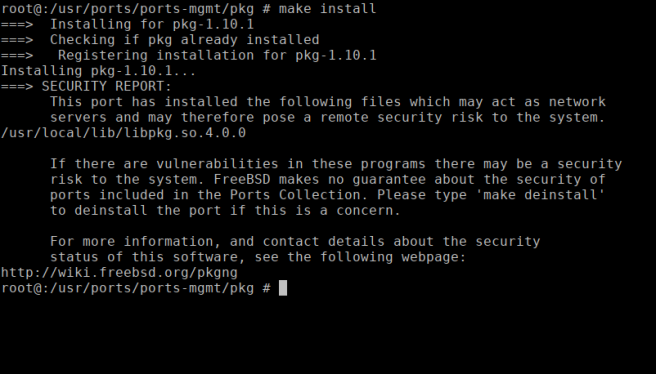

On my fresh example system I build the Pkg manager from ports first – it’s needed for every other port anyway. Once everything has finished I get my shell back.

Installing the program is just as easy: Use make install

Installing the newly built port

Installing the newly built port

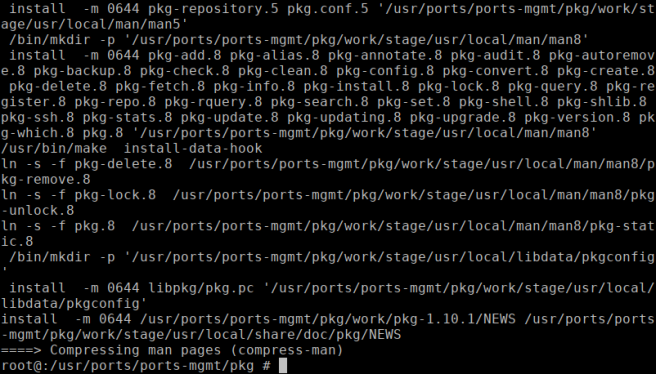

That’s it, Pkg is now installed. We’re basically done with that port. However there’s still the “work” directory left over from the building process. To tidy up our port’s directory we can issue make clean.

Dependency handling

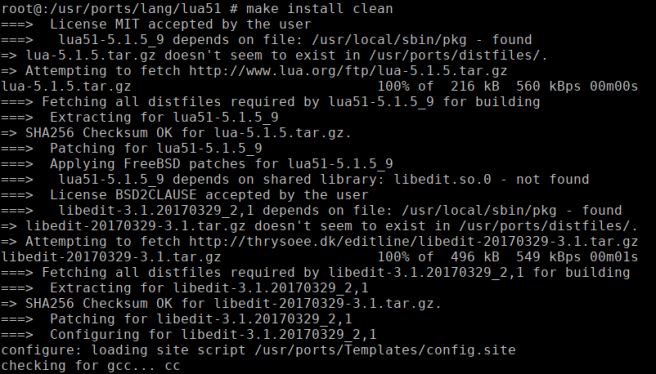

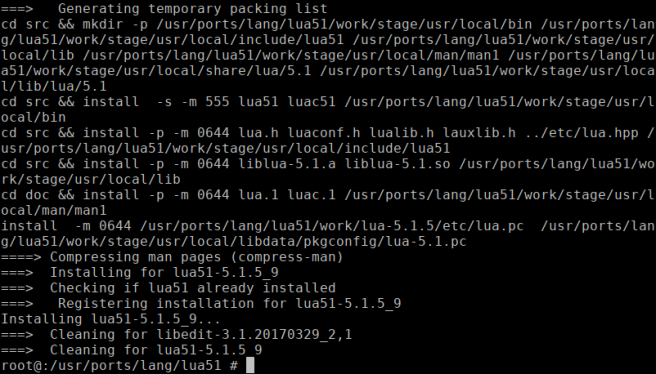

On to a just slightly more complex example. I want to build and install an old version of the LUA interpreter which depends on another port, libedit. Of course I could build devel/libedit first and then lang/lua51. In that case it wouldn’t be so bad. But if you think of larger programs with hundreds of dependencies that approach would be a nightmare.

So what to do about it? Well, nothing actually. The ports system takes care of it automatically! Just have it build LUA and it will figure out that it has to build the dependency first.

Building, installing and cleaning up in one command

Building, installing and cleaning up in one command

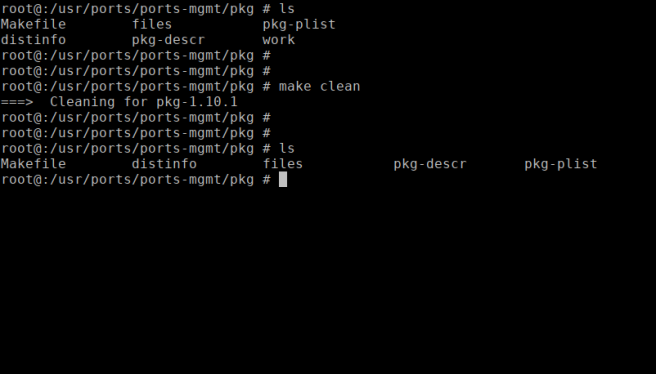

The parameters to make that we used above are called make targets, BTW, and can be combined. That means it’s perfectly fine to issue make install clean together as you can see in the picture above.

Dependencies are handled automatically

Dependencies are handled automatically

The clean make target is also applied to all ports that were built as a dependency for the current port. Things like this make ports very convenient to use.

More on make and targets

Make targets can depend on other make targets. When you issue make install these are the targets that are actually run:

- make config (more on that in a minute)

- make fetch (fetch all files needed to build the port)

- make checksum (check integrity of downloaded file(s))

- make depends (check for missing dependencies and build/install those)

- make extract (extract distfile(s) for the port)

- make patch (apply patches for this port, if any)

- make build (actually build the port)

- make install (install the newly-built program)

If you type make checksum for example, all targets up to and including that one will run (that is config, fetch and checksum in that case). Running just make without any target will assume the default target which is equivalent to make build.

Also make will take an argument to look for the Makefile in another directory if you wish. So instead of doing e.g. this:

# cd /usr/ports/archivers/bzip2 # make install clean

you could also simply do this:

# make -C /usr/ports/archivers/bzip2 install clean

You’re in control: Ports options

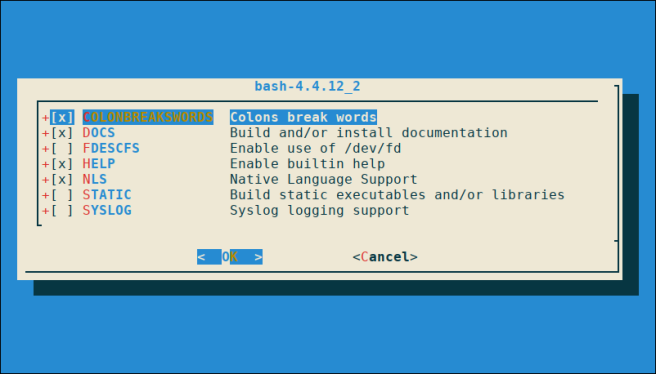

So far it’s all nice and well but there’s no real advantage to using ports instead of packages. May I introduce ports options? Let’s say you we want to build BASH. If issue make in shells/bash, this is what happens:

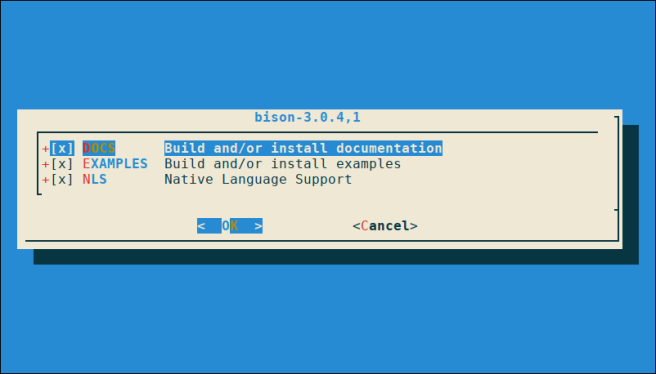

The port ports-mgmt/dialog4ports is fetched and installed. It’s so small that you might miss it but it’s quite important. It’s needed to display the menu in the picture above which lets you set various options for the port.

You can now e.g. choose to not install the documentation if you’re short on space on a small or embedded system (sure, you wouldn’t actually compile on such a system, but that’s only an example, right?). If you don’t want BASH to support any foreign languages, deselect NLS. In case you feel that BASH’s built-in help is useless (did you ever issue the help command when you ran BASH?), you can cut that feature. Things like that.

If you see the option configuration for a port the first time, you see the default configuration. In general it’s a good idea to leave options alone if you’re in doubt what they do (do a little research if you have the time). Of course you’re also free to experiment with them. It’s your system.

Once you’re happy, accept your selection and the source tarball is being fetched, extracted, etc. You know the score.

But what’s that? Another configuration menu (for bison)? And another (m4) and another (texinfo), etc… It’s 8 menus for a rather basic program like BASH! And worse: The building process will run and build dependencies and when a port with options is reached, the process is interrupted and prompts the user.

Now imagine you’re building a whole graphical desktop like MATE… Currently even the basic desktop would build no less that 338 dependency packages on a fresh system! And there’s quite a few ports on the list which build rather heavy software that takes it’s time compiling. It would totally make sense to let it build over night or at least not require you to keep staring at the screen, waiting for the next options selection to confirm, right?

Recursive operations

Exactly that’s why recursive operations are supported by the ports system. The standard make target that was implicitly run to open the options dialog is make config. The recursive option which would run the same on each and every port that’s listed as a dependency for the current port is make config-recursive.

If you want to build MATE as mentioned in the previous example, that would start a true marathon of options for you to configure. However it’s still a lot better to be able to do this up front so that the build process can run uninterruptedly afterwards.

Oh, and don’t be surprised if you went through it all only to find that still another configuration dialog pops up later! Why? Most likely you enabled an option on some package that made it depend on another package that’s not a dependency by default. And that package may need to have its options configured, too. So if you changed any options it makes sense to run make config-recursive again until no more new option dialog windows are displayed!

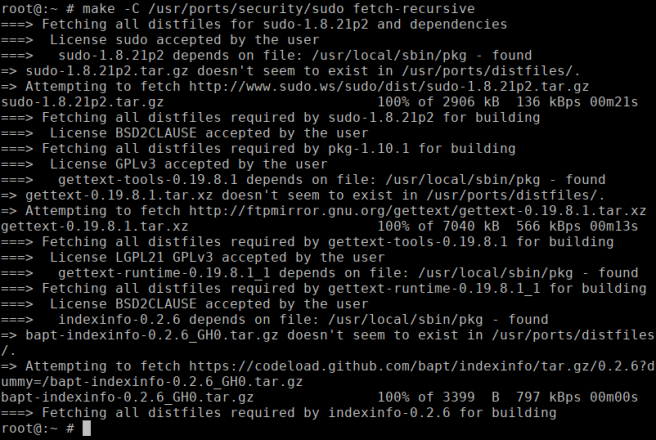

Recursively fetching distfiles for security/sudo

Recursively fetching distfiles for security/sudo

You can also do make fetch-recursive to fetch the distfiles for the current port and all dependencies. Again: Keep in mind that enabling more options may lead to new dependencies. If you want to make sure that you have all the distfiles, you might want to run make fetch-recursive again after changing ports options.

Other things to know

Wonder where the all the options are saved? They are stored in text files in /var/db/ports/category_portname. But there’s no need to edit or delete them; if you want to get rid of them, there’s make rmconfig to do that. Also make rmconfig-recursive exists if you feel like blowing away a huge amount of them.

Ports options in /var/db/ports

Ports options in /var/db/ports

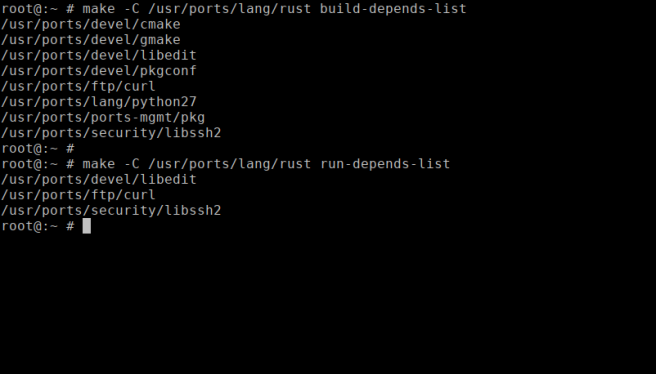

Another thing that comes in handy is make build-depends-list which will show you a list of ports that will be built as build dependencies for your current port. If you want to see the runtime dependencies you would use make run-depends-list. And then there’s also make all-depends-list which will show you each and every port that would be installed if you chose to build the current port.

You should also know that you can deinstall a port by using make deinstall. Yes, it is also possible to remove the package using pkg delete but that will lead to a problem. The ports infrastructure keeps track of installed ports separately and Pkg does not know anything about this. So even if your package is removed, the Ports infrastructure will insist that it is still installed and there’s something very wrong with your system!

Now what to do if you have that case? Use make reinstall to install the package again even though ports thinks that it’s already installed.

More on ports?

To be honest, there’s quite a bit more to ports than I could cover here. You may want to man 7 ports to see what other targets are available and what they do. Also we haven’t even touched how to keep your system updated when using ports!

The ports infrastructure is a great means of installing customized programs on your system. It’s quite easy to use as you’ve seen. But things can be made even easier – which is why there are helper tools available. I will write a follow-up article covering those (not the next one, though). But for now enjoy all of those new possibilities with software on your FreeBSD machines!

Nice one. I think you’re really on to something with your breezy writing and composition style — I’m certainly digging it — and the shift towards the BSDs isn’t hurting imho (come hither, systemd refugees…). Looking forward to your take (always time and willingness permitting, of course) on such possible subjects as: the BSD permissive licence v GPL thing, which bsd firewall?, well, systemd too if that’s not too destructive an issue… there’s so much to talk about as we near 2018.. and of course you’re building the blog up towards “BSD from scratch”, aren’t you.

Aren’t you. ..hello?

Anyone there? lol

Haha! Thanks for your comment! Glad you like my “style” – or lack thereof since I’m hardly comfortable writing in English (at least not enough to consider things like style). 😉 I do try to avoid writing completely boring, though, and hope to convey a bit of my passion for the topics I write about.

Honestly, I’ve thought about “BSD from scratch” as an April fool. Might still do this somewhen, making a little fun of LFS (I do have a lot of respect for that project, though). It would essentially just cover getting the source from SVN, building world and kernel and then installing that into another partition – and than compare that to the LFS book. *g* Of course it could be done more seriously, too, discussing NanoBSD and the various components of the base system. That could actually be pretty interesting, but I lack the knowledge to do something like that (at least for the time being!).

About BSD vs. GPL: I have an article about that in mind now since… Gimme a second, have to look it up… Gosh, 2014! Never found time for it as other topics always jumped the queue! But I’ll try to make room. Firewalls: Would be very interesting, but it’s a big topic and would need quite a bit of preparation (I’m not very familiar with IPFW or even the old IPF). And Systemd… Well, I could certainly say something about it. Actually I have to admit that I… uhm, kind of liked it when it first came to Arch Linux. It took me a while to realize that it’s a monstrosity. But let’s see which topics eventually emerge. I’m very happy to see that people are interested in the same topics that I am and I’ll definitely continue to write about *nix topics.

For anyone who wants to build ports with tweaked options while essentially still managing things using pkg, I’d recommend giving synth a try.

Agreed. I intend to write one follow-up about Portmaster and Portupgrade and then compare Poudriere and Synth. Eventually I want to write about building packages for OPNsense with Synth, which is why I started this series on package management / Ports in the first place.